Introduction to LaMa

Jan-Ole Koslik

Intro_to_LaMa.RmdThe R package LaMa provides convenient

functions for fitting a variety of latent Markov models

(Mews, Koslik, and

Langrock 2025), including hidden Markov

models (HMMs), hidden semi-Markov models

(HSMMs), state space models (SSMs) and

continuous-time variants via direct numerical

maximum likelihood estimation. The core idea is that the user

defines their own negative log-likelihood function for numerical

optimisation, but can rely on package functions for convenience and

speed.

The main families of functions are forward,

tpm and stationary and we showcase the

simplest versions in the following introductory example.

Introductory example: Homogeneous HMM

In this vignette, we start from the most simple HMM we can think of. Such a basic N-state HMM is a doubly stochastic process in discrete time. Observations are generated by one of N possible distributions f_j(x_t), j = 1, \dots N with an unobserved N-state Markov chain selecting which distribution is active at any given time point. Hence, HMMs can be interpreted as temporally dependent mixture models and are very popular across a wide range of disciplines like ecology, sports and finance where time-series data with underlying sequential dependencies are to be analysed. They statements above already hint at the two main assumptions in such a model, namely

- f(s_t \mid s_{t-1}, s_{t-2}, \dots, s_1) = f(s_t \mid s_{t-1}) (Markov assumption)

- f(x_t \mid x_1, \dots, x_{t-1}, x_{t-1}, x_T, s_1, \dots, s_T) = f(x_t \mid s_t) (conditional independence assumption).

The hidden state process is described by a Markov chain, as such a

stochastic process can easily be characterised by its initial

distribution \delta^{(1)} = (\Pr(S_1

= 1), \dots, \Pr(S_1 = N)) and the one-step transition

probabilities \gamma_{ij} = \Pr(S_t

= j \mid S_{t-1} = i), \quad i,j = 1, \dotsc, N which are

typically summarised in the so-called transition probability

matrix (t.p.m.) \Gamma =

(\gamma_{ij})_{i,j = 1, \dots, N} where row i is the conditional one-step ahead

distribution of the state process given that the current state is i. Such a matrix is most-conveniently

parameterised by an unconstrained parameter vector for the N (N-1) off-diagonal elements. Each row can

then be computed via the inverse multinomial logistic link (also known

as softmax). This can be done using the function tpm():

(Gamma = tpm(c(-2, -3))) # 2 states -> 2*(1-2) = 2 off-diagonal entries

#> S1 S2

#> S1 0.9525741 0.04742587

#> S2 0.1192029 0.88079708For HMMs with such homogeneous transition probabilities, we often

assume stationarity of the underlying Markov chain, as

well-behaved Markov chains converge to a unique stationary distribution.

When we e.g. observe an animal and model its behavioral states by a

Markov chain, it is reasonable to assume that the chain has been running

for a long time prior to our observation and thus already converged to

its stationary distribution. This distribution (which we call \delta) can be computed by solving the system

of equations

\delta \Gamma = \delta, \quad \text{s.t.} \; \sum_{j=1}^N \delta_j = 1,

which is implemented in the function stationary().

For stationary HMMs, we then replace the initial distribution \delta^{(1)} by this stationary distribution.

We can easily compute the stationary distribution associated with the

above t.p.m. using

(delta = stationary(Gamma))

#> S1 S2

#> 0.7153801 0.2846199This stationary distribution can be interpreted as the log-run-time proportion of time spent in each state.

For the conditional distributions of the observations f_j(x_t), a typical choice would be some kind of parametric family like normal or gamma distributions with state-specific means and standard deviations. For a more exhaustive description of such models see Zucchini, MacDonald, and Langrock (2016).

Generating data from a 2-state HMM

We start by simulating some data from a simple 2-state HMM with

Gaussian state-dependent distributions, to get some intuition. Here we

can again use stationary() to compute the stationary

distribution.

# parameters

mu = c(0, 6) # state-dependent means

sigma = c(2, 4) # state-dependent standard deviations

Gamma = matrix(c(0.95, 0.05, 0.15, 0.85), # transition probability matrix

nrow = 2, byrow = TRUE)

delta = stationary(Gamma) # stationary distribution

# simulation

n = 1000

set.seed(123)

s = rep(NA, n)

s[1] = sample(1:2, 1, prob = delta) # sampling first state from delta

for(t in 2:n){

# drawing the next state conditional on the last one

s[t] = sample(1:2, 1, prob = Gamma[s[t-1],])

}

# drawing the observation conditional on the states

x = rnorm(n, mu[s], sigma[s])

color = c("orange", "deepskyblue")

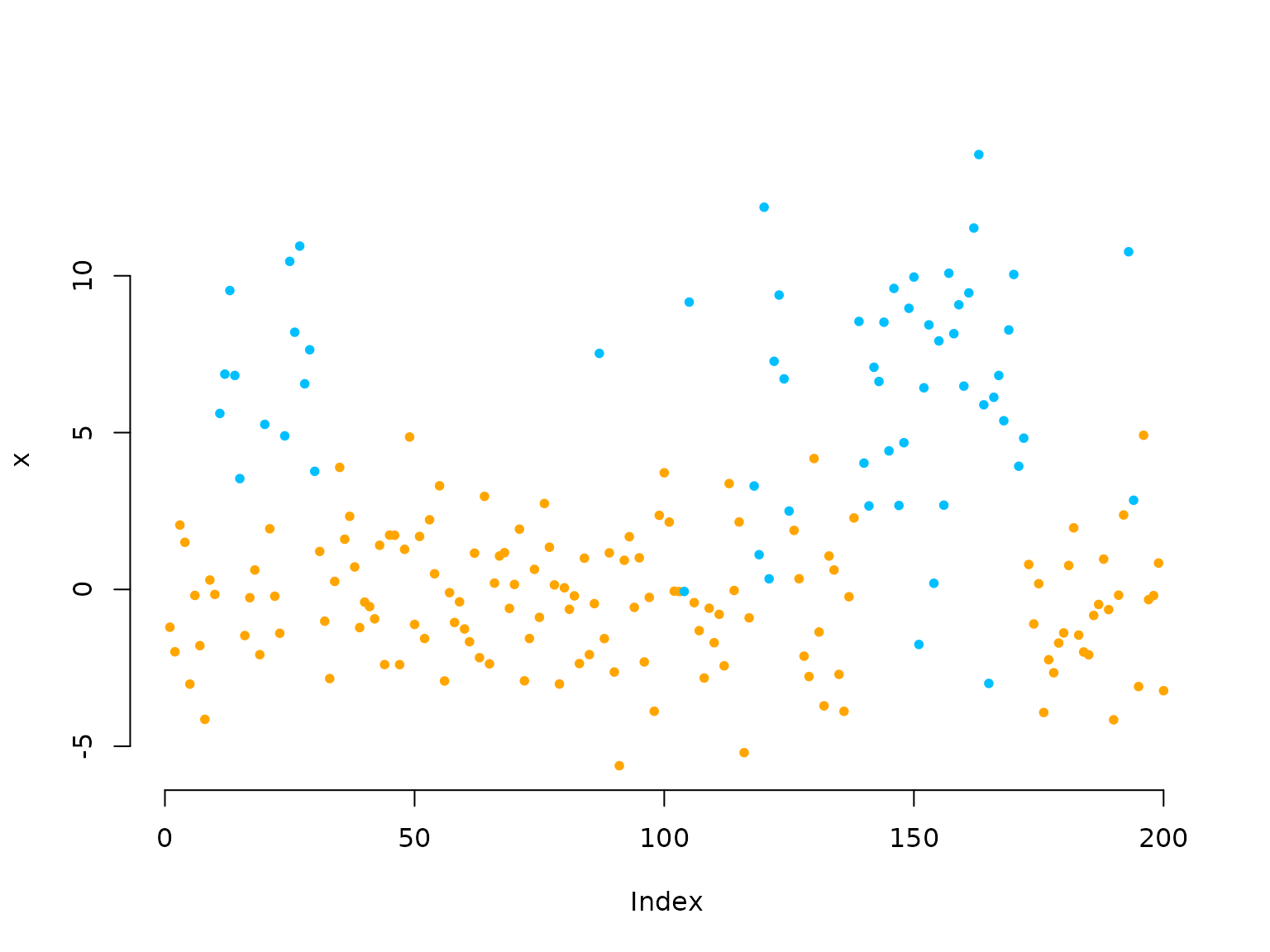

plot(x[1:200], bty = "n", pch = 20, ylab = "x",

col = color[s[1:200]])

Inference by direct numerical maximum likelihood estimation

Inference for HMMs is more difficult compared to e.g. regression modelling as the observations are not independent. We want to estimate model parameters via maximum likelihood estimation, due to the nice properties possessed by the maximum likelihood estimator. However, computing the HMM likelihood for observed data points x_1, \dots, x_T is a non-trivial task as we do not observe the underlying states. We thus need to sum out all possible state sequences which would be infeasible for general state processes. We can, however, exploit the Markov property and thus calculate the likelihood recursively as a matrix product using the so-called forward algorithm. In closed form, the HMM likelihood then becomes

L(\theta) = \delta^{(1)} P(x_1) \Gamma P(x_2) \Gamma \dots \Gamma P(x_T)

1^t,

where \delta^{(1)} and \Gamma are as defined above, P(x_t) is a diagonal matrix with

state-dependent densities or probability mass functions f_j(x_t) = f(x_t \mid S_t = j) on its

diagonal and 1 is a row vector of ones

with length N. All model parameters are

here summarised in the vector \theta.

Being able to evaluate the likelihood function, it can be numerically

maximised by popular optimisers like nlm() or

optim().

The algorithm explained above suffers from numerical underflow and

for T only moderately large the

likelihood is rounded to zero. Thus, one can use a scaling strategy,

detailed by Zucchini, MacDonald, and Langrock (2016), to avoid this and calculate the

log-likelihood recursively. This version of the forward algorithm is

implemented in LaMa and written in C++.

Additionally, for HMMs we often need to constrain the domains of

several of the model parameters in \theta (i.e. positive standard deviations or

a transition probability matrix with elements between 0 and 1 and rows

that sum to one). One could now resort to constrained numerical

optimisation but in practice the better option is to maximise the

likelihood w.r.t. a transformed version (to the real number line) of the

model parameters by using suitable invertible and differentiable link

functions (denoted by par in the code). For example we use

the log-link for parameters that need to be strictly positive and the

multinomial logistic link for the transition probability matrix. While

the former can easily be coded by hand, the latter is implemented in the

functions of the tpm family for convenience and

computational speed.

For efficiency, it is also advisable to evaluate the state-dependent

densities (or probability mass functions) vectorised outside the

recursive forward algorithm. This results in a matrix containing the

state-dependent likelihoods for each data point (rows), conditional on

each state (columns), which, throughout the package, we call the

allprobs matrix.

In this example, within the negative log-likelihood function we build

the homogeneous transition probability matrix using the

tpm() function and compute the stationary distribution of

the Markov chain using stationary(). We then build the

allprobs matrix and calculate the log-likelihood using

forward() in the last line. It is returned negative such

that the function can be numerically minimised by

e.g. nlm().

nll = function(par, x){

# parameter transformations for unconstrained optimisation

Gamma = tpm(par[1:2]) # multinomial logistic link

delta = stationary(Gamma) # stationary initial distribution

mu = par[3:4] # no transformation needed

sigma = exp(par[5:6]) # strictly positive

# calculating all state-dependent probabilities outside the forward algorithm

allprobs = matrix(1, length(x), 2)

for(j in 1:2) allprobs[,j] = dnorm(x, mu[j], sigma[j])

# return negative for minimisation

-forward(delta, Gamma, allprobs)

}Fitting an HMM to the data

par = c(logitGamma = qlogis(c(0.05, 0.05)),

mu = c(1,4),

logsigma = c(log(1),log(3)))

# initial transformed parameters: not chosen too well

system.time(

mod <- nlm(nll, par, x = x)

)

#> user system elapsed

#> 0.125 0.010 0.134We see that implementation of the forward algorithm in C++ leads to really fast estimation speeds.

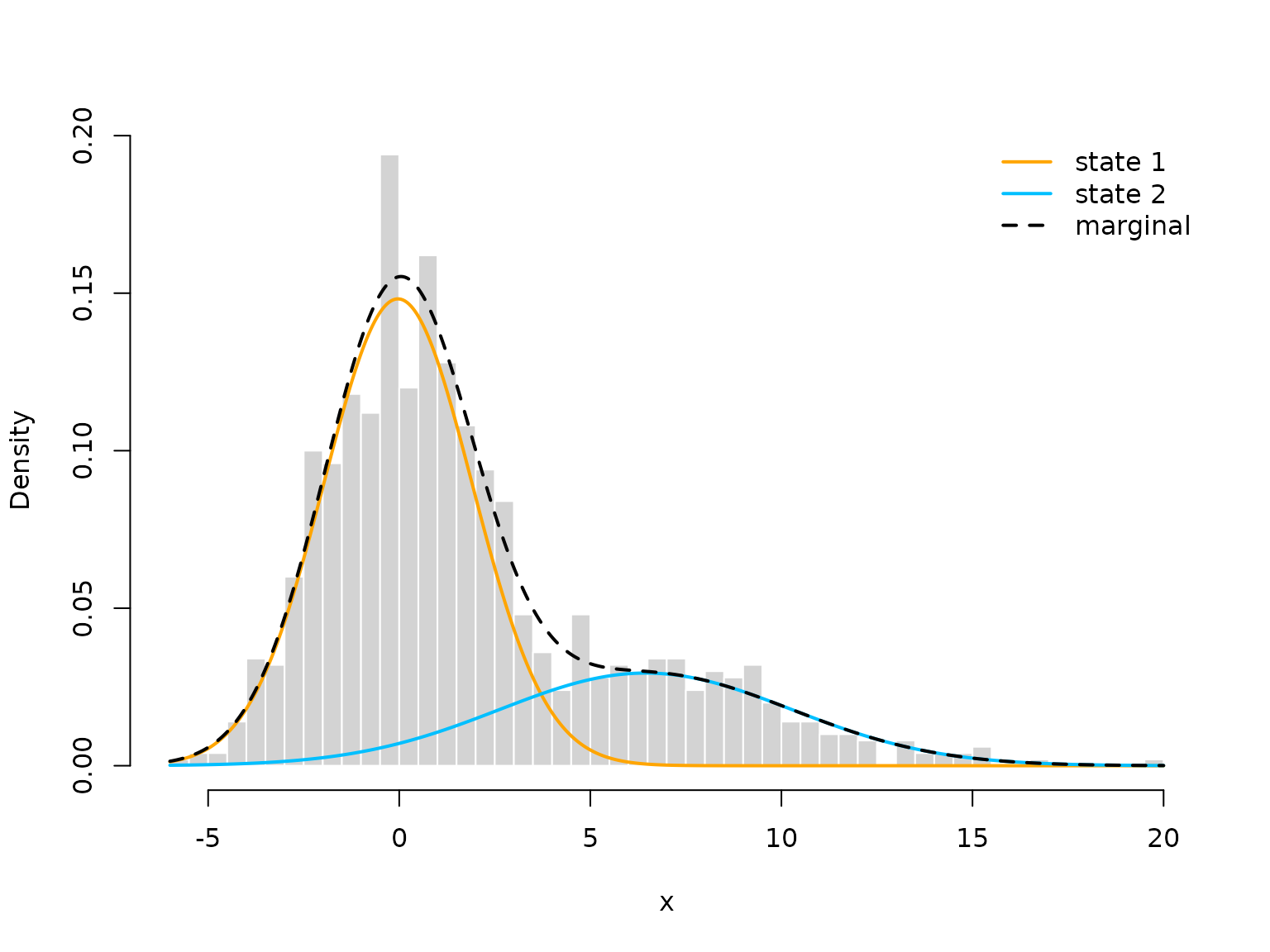

Visualising results

After model estimation, we need to retransform the unconstrained parameters according to the code inside the likelihood:

# transform parameters to working

Gamma = tpm(mod$estimate[1:2])

delta = stationary(Gamma) # stationary HMM

mu = mod$estimate[3:4]

sigma = exp(mod$estimate[5:6])

hist(x, prob = TRUE, bor = "white", breaks = 40, main = "")

curve(delta[1]*dnorm(x, mu[1], sigma[1]), add = TRUE, lwd = 2, col = "orange", n=500)

curve(delta[2]*dnorm(x, mu[2], sigma[2]), add = TRUE, lwd = 2, col = "deepskyblue", n=500)

curve(delta[1]*dnorm(x, mu[1], sigma[1])+delta[2]*dnorm(x, mu[2], sigma[2]),

add = TRUE, lwd = 2, lty = "dashed", n=500)

legend("topright", col = c(color, "black"), lwd = 2, bty = "n",

lty = c(1,1,2), legend = c("state 1", "state 2", "marginal"))

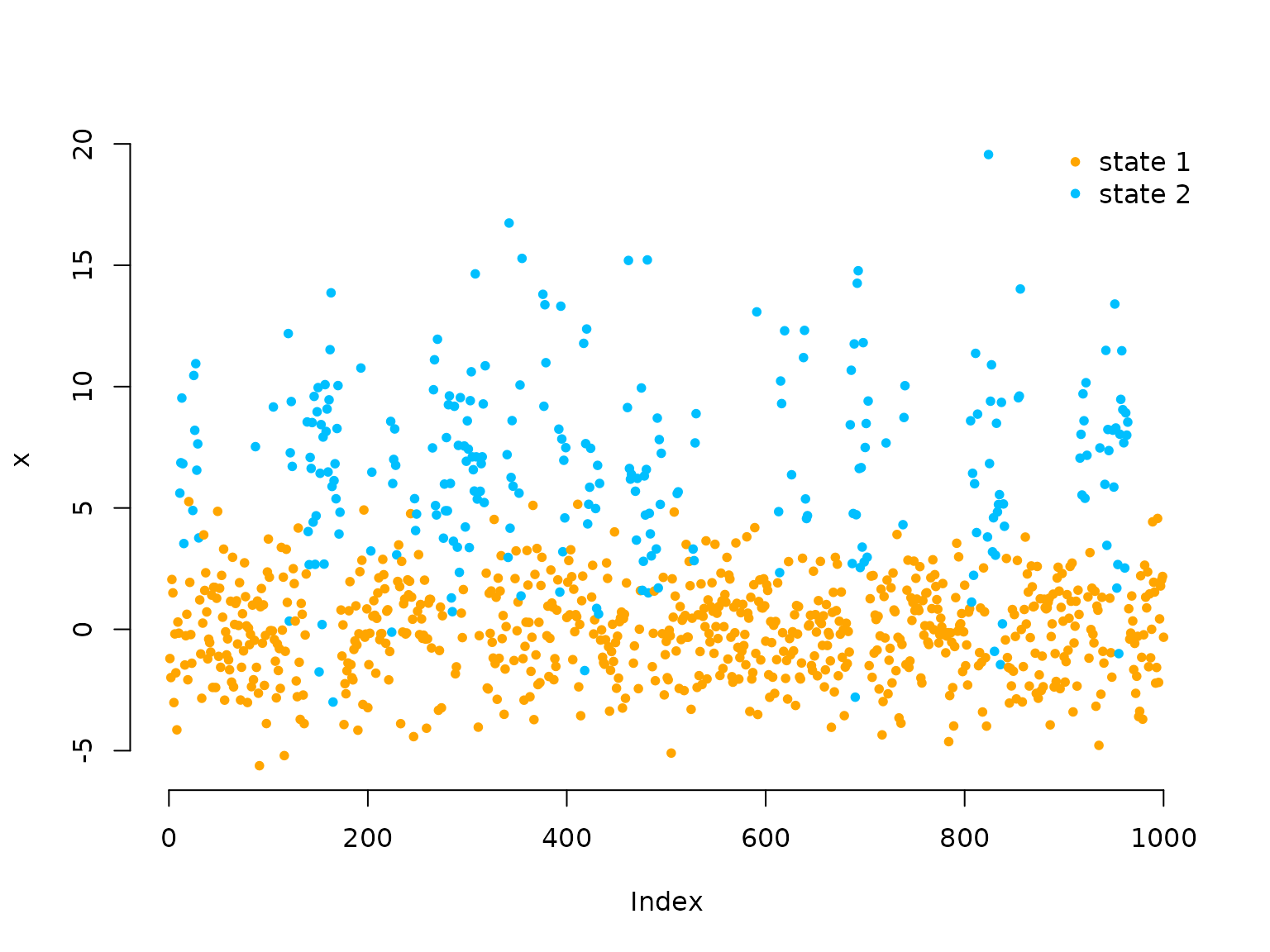

We can also decode the most probable state sequence with the

viterbi() function, when first computing the

allprobs matrix:

allprobs = matrix(1, length(x), 2)

for(j in 1:2) allprobs[,j] = dnorm(x, mu[j], sigma[j])

states = viterbi(delta, Gamma, allprobs)

plot(x, pch = 20, bty = "n", col = color[states])

legend("topright", pch = 20, legend = c("state 1", "state 2"),

col = color, box.lwd = 0)

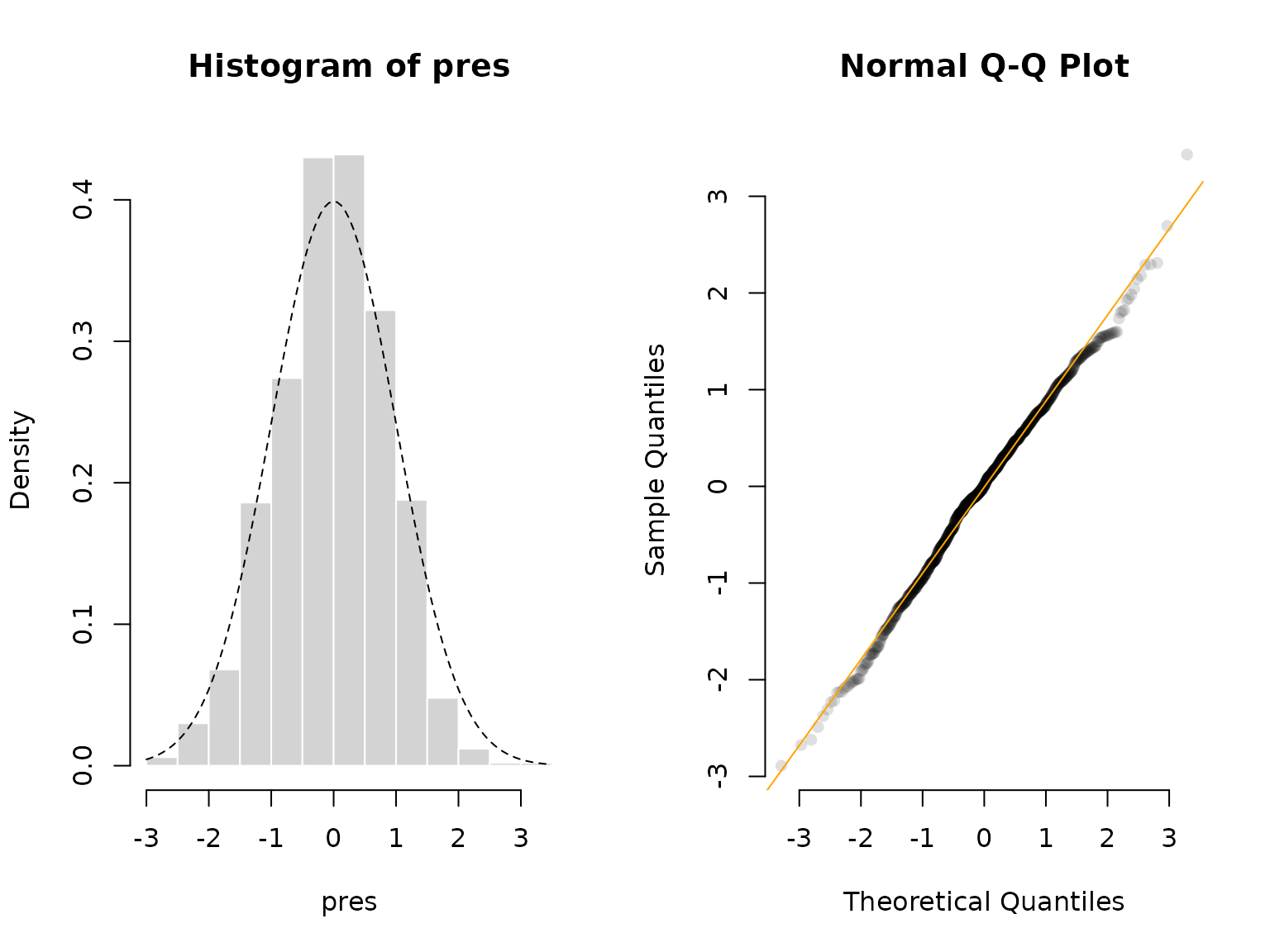

Lastly, we can do some model checking using pseudo-residuals. First, we need to compute the local state probabilities of our observations:

probs = stateprobs(delta, Gamma, allprobs)Then, we can pass the observations, the state probabilities, the

parametric family and the estimated parameters to the

pseudo_res() function to get pseudo-residuals for model

validation. These should be standard normally distributed if the model

is correct.

pres = pseudo_res(x, # observations

"norm", # parametric distribution to use

list(mean = mu, sd = sigma), # parameters for that distribution

probs) # local state probabilities

# use the plotting method for LaMaResiduals

plot(pres, hist = TRUE)

In this case, our model looks really good – as it should because we simulated from the exact same model.

Continue reading with LaMa and RTMB, Inhomogeneous HMMs, Periodic HMMs, Longitudinal data, State-space models, Hidden semi-Markov models, or Continuous-time HMMs.